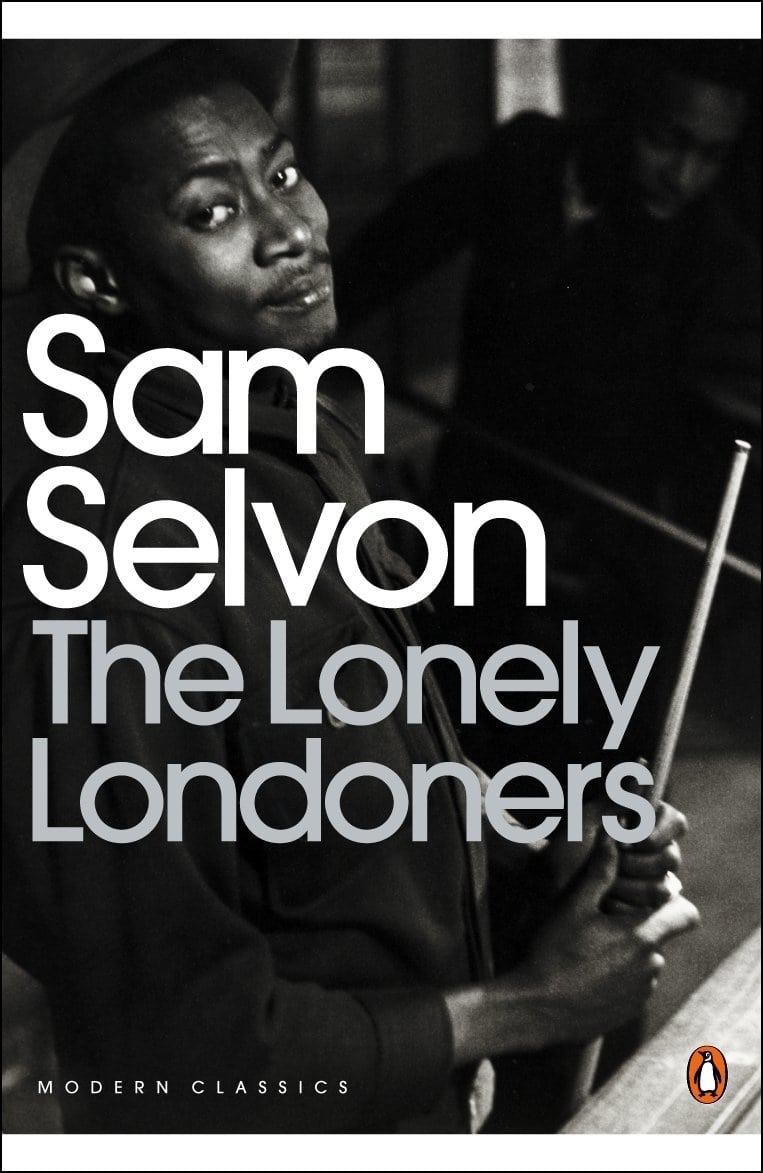

The recent Windrush scandal cast Sam Selvon’s novel The Lonely Londoners back into the spotlight as it became clear that those who had left the Caribbean in search of a better life remained subject to the same kind of discrimination that Selvon had described 60 years earlier.

The fact that thousands of West Indians who had helped forge modern Britain were still regarded as insufficiently British to stave off the threat of deportation caused uproar. In response, the University’s English department wrote an open letter expressing support for the Windrush generation, a statement influenced not just by the injustice itself but also by the University’s links to the author of The Lonely Londoners.

It was in 1975, almost two decades after Selvon’s book saw him heralded as one of the most exciting novelists in post-war Britain, that he took up a post as Creative Writing Fellow at Dundee. He was to prove a hugely popular figure during his time at Dundee, a two-year stint that also saw him dispense advice to would-be writers loaded up with children and shopping, become embroiled in a dispute over office accommodation, and apply coats of emulsion to an old East Neuk fishing cottage.

From Port of Spain to Notting Hill

Long before he himself ventured forth from his home island, Samuel Dickson Selvon was aware of the immigrant experience. He was born in 1923 to Indian parents, themselves of Anglo-Scottish heritage, who had set up home in Trinidad. Trinidad and Tobago was then a British colony and Selvon worked as a wireless operator with the local branch of the Royal Naval Reserve during the Second World War. Afterwards, he became a journalist and made his first literary forays, writing stories under a variety of pseudonyms, before moving to London in 1950.

Selvon found work at the Indian Embassy while continuing to write in his spare time. His short stories and poetry appeared in various publications while his debut novel, A Brighter Sun, was published in 1952. Positive reviews persuaded Selvon to try his luck as a full-time writer, and a further two books followed in the next three years. It was the 1956 publication of The Lonely Londoners, however, that established its author as one of the foremost chroniclers of the Windrush generation and their struggles to adapt to life in the ‘Mother country.’

The Financial Times called it “the definitive novel about London’s West Indians”, while for the Guardian Selvon’s masterpiece was “a vernacular comedy of pathos” due to its pioneering use of Caribbean creole throughout. This and the unconventional subject matter lent The Lonely Londoners an authenticity lacking in most contemporaneous accounts of the lives of these newcomers to Britain.

Selvon later acknowledged that “the people I wanted to describe were entertaining people indeed, but I could not really move. At that stage, I had written the narrative in English and most of the dialogues in dialect. Then I started both narrative and dialogue in dialect and the novel just shot along.”

The impact was significant, as one commentator noted recently: “his success in using the idiom stimulated the linguistic liberation of Caribbean and other non-British writing from the bonds of ‘standard English’. His importance has been increasingly recognised.”

The world-weary Moses, naive Galahad, formidable Tanty and a host of other richly drawn characters gave a voice to the voiceless just as the infamous ‘No Blacks, No Dogs, No Irish’ signs went up in boarding room windows across Britain. There was a tendency even among well-meaning commentators to infantilise the immigrants, but Selvon’s Lonely Londoners were never sentimentalised. Individuals could be aloof, generous, prejudiced, compassionate, romantic or exploitative, or more likely a combination of all these traits and many more besides. In short, they were complex rather than caricatures. In recounting the hardships, mishaps, prejudice and comradeship they encountered, the book was as hilarious as it was heart-rending.

Over the next 20 years, Selvon published a further six novels, produced a collection of short stories, penned BBC television plays and a co-wrote the screenplay for Pressure, a critically acclaimed film centred around Tony, a black teenager who was the first of his Trinidadian family to be born in Britain. Pressure revisited similar themes to the ones Selvon first explored in what remains his best-known and most-celebrated book and was last year ranked as one of the 50 best British films of all time.

The journey continues

Pressure, the first black-directed (by Horance Ove) British feature-length fiction film, was shelved by funders BFI for almost three years due to controversial scenes of police brutality directed against the black community. By the time it was finally released in October 1976, Sam Selvon had been working at Dundee for a year.

The Fellowship came with an annual salary of £2202 – nearly £22,000 in today’s money – which was bolstered by the provision of a three-bedroom flat at 516 Perth Road offering enviable views over the nearby Botanic Garden and River Tay. The Scottish Arts Council (SAC) provided £1250 towards the cost of employing the Fellow, with the remainder being met by the University.

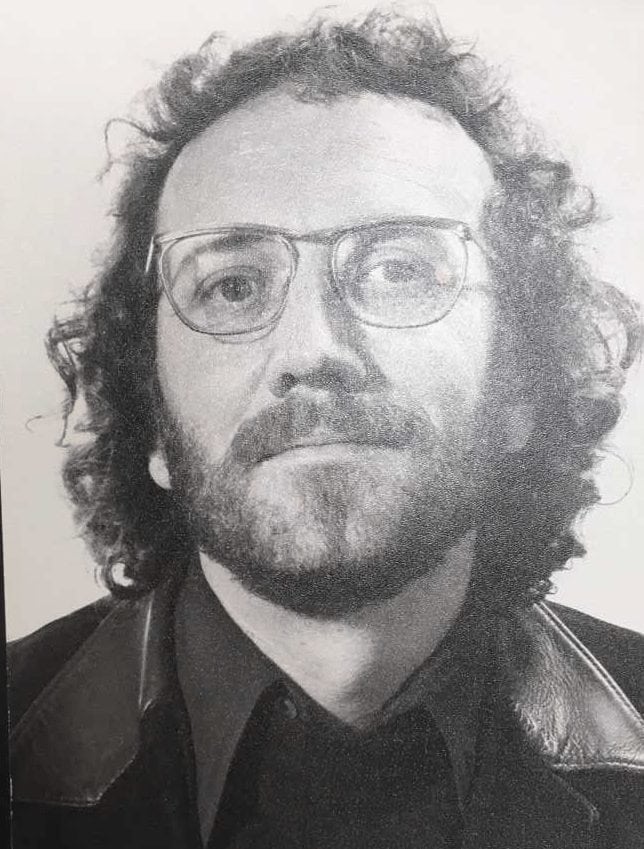

Selvon’s successor as the Creative Writing Fellow was Carl McDougall (pictured below right), who would go on to establish himself as a respected short story writer and novelist. The pair met shortly after Selvon took up his post at Dundee and quickly struck up a friendship.

He recalled, “At the time I had just started Words, the first Scottish literary magazine to publish short stories regularly. We had extracts from Lanark and it’s where James Kelman and Alexander McCall Smith were first published and when Sam was appointed to his post at Dundee I asked him to come over to Fife and do a reading for us.

“Afterwards I gave him a copy of Words and he said he really liked one of my stories. From then he came over to eat with us regularly. We were in the process of doing up an old house in Crail that we had just bought and he even helped us do some of the painting.

“Most of my students had gone to Sam’s class and he was a very popular teacher. He was sympathetic and supportive, and he certainly helped my writing a lot. Sam never directly criticised your work, but you always left discussions with him with a clear impression of the ideas he thought it would be worth you considering.”

Selvon hosted a two-hour Writing Workshop each Wednesday while also making himself available for anyone seeking his advice at other times. The Creative Writer was expected to work with members of the public seeking to develop their writing skills as much as students. An insight into what this meant in practice came in a formal protest Selvon lodged against proposals to remove the English staff from their base at 6 Perth Road as part of a convoluted reallocation of office space that also affected the Economics and French departments.

The memo, held in the University’s Archives collection, sees Selvon, who was due to vacate the post within a matter of months, fight the corner of his successor, writing, “The room intended for the Creative Writer is at least two and a half times smaller than the present office, which would be completely hopeless to encompass the range of work involved in this appointment.

“The success of the weekly Writers’ Workshop is in great measure due to the location of the present office near, but not in, the main buildings of the University. Sometimes people come in with their children and shopping … I would like this matter to be re-considered.”

The campaign proved successful, as Carl took up the office vacated by Selvon on his appointment. He was unsurprised to see his friend railing against authority. “I always got the feeling he was never entirely at home in a University setting,” he said. “Like me, Sam had never been a student at one, so I’m not sure how comfortable he was here in that sense. His family were still staying in London so he used to stay at the Perth Road flat in the latter half of each week before going back down the road to them at weekends.”

In addition to his teaching work, Selvon contributed short stories to the University Arts magazine, Gallimaufry, and his book Those who Eat the Cascadura was given as a prize to the best contribution to the Spring 1976 edition of that publication.

Ever northwards

Shortly after leaving Dundee, Selvon moved to Canada. Whatever reservations Carl felt his mentor may have harboured towards academia, appeared to have been forgotten and he taught creative writing at the University of Victoria before becoming writer-in-residence at the University of Calgary.

Selvon died while on a visit to Trinidad in April 1994 at the age of 70, having published two further novels and two collections of plays since his time at Dundee.

At the time of his friend’s death, Carl paid tribute to “one of the most generous men I have ever met”, saying, “He must have spent hours discussing other people’s work … with warmth, sensitivity and humour.”

His impact was powerful in a small community, a place with a distinctive voice and little means of expressing it. He encouraged others to find their voice through the voice of their community.

– Carl McDougall

“I have lost count of the people he helped into print. Numbers hardly matter. Everyone was treated the same. He offered improvement or suggested a practical means of publication because he was that sort of man. He couldn’t help himself.”

Sam Selvon’s death came before the Internet entered into common usage so he would likely have been flummoxed by the concept of a Google Doodle celebrating his literary achievements on what would have been his 95th birthday. He would surely be delighted that his work remains cherished by so many, though dismayed that the issues he held a mirror to more than 60 years ago remained topical in today’s Britain.

In The Lonely Londoners, Selvon said of the British weather, “sometimes the words freeze and you have to melt it to hear the talk”, illustrating how his own words were anything but cold. Each page crackled with the creole he so beautifully used to capture the voice of the Windrush generation. Through his pioneering use of language, stereotypes were demolished and “the boys” were humanised at a time when they were too often seen as little more than an amorphous mass of delinquency and deviancy.

Since his death, the Samuel Selvon Memorial Prize has been awarded each year to the most outstanding final year undergraduate English student at Dundee. Though his time at the University was brief he helped many, and it is right we celebrate our links to this remarkable writer.

I was a member of the University Writing class in the 1970s run by Carl MacDougall who was enormously influential in my development as a writer. I had met Selvon and much much later, when I returned to the University to do a degree, won, in my Hons year, 1997, the Sam Selvon Prize for English. As a long-term admirer of his novels, Turn Again Tiger, Ways of Sunlight and Lonely Londoners, I was hugely aware of the honour. Carl was very generous with his time and helped students in the class set up a literary magazine AMF (later returned) Logos which ran to 11 issues and proved influential. Great days. I have been able to provide an overview of these literary events in my two-volume Literary Lives of Dundee (AHS, 2003/4).