Policies. You may not have noticed but we’ve got a lot of these on the website. Not just policies but other types of corporate information like procedures, regulations, disclaimers, reports, rules, statutes, templates, codes of conduct, classification schemes, privacy notices – stay with me this gets much more interesting, I promise.

This university, like all others, produces mountains of this stuff. How we manage this kind of content is something that has preoccupied this team recently.

Take a random sample of university websites and you’ll be lucky to find any instances of institutions presenting clear, accessible, well organised and structured policy content. We want to change this. However, it’s not without its challenges.

There’s a view that it’s typically the content that people care least about. Why is this?

Typically it’s wordy with long sentences and dense paragraphs. The legalese nature of the content often makes it the opposite of plain English. It’s commonly the output of committees which, to be blunt, are dull.

But dull content can have its uses.

Dull content is often important content.

Dull content matters.

Why it matters

It’s important that publicly funded institutions and organisations (and universities come into this category) are transparent about how they operate and are governed. This means that items like policies and procedures need to be published on the website. And kept up to date.

From a user perspective, corporate information can be important content too. This is especially the case when something goes wrong or perhaps something changes in a person’s circumstances.

It’s worth considering a user’s emotional state when they are trying to find a policy on a website. An employee who is anxious and worried because of changes in their personal life may become even more upset if they can’t find a work/life balance policy for their organisation.

When policies matter to website users, they tend to really matter. And the frustration people feel when they can’t locate information easily only compounds what is already a stressful situation.

Don’t make me think

The information architecture of traditional organisational websites often forces users to navigate and understand the organisational hierarchy to access crucial information like policies. Unwittingly they make it difficult for users by publishing the information in silos across the website.

Information foraging

Improving how users find this content is one part of our challenge. Another is making it easier to recognise and understand the content when they come across it.

Imagine a user journey as a series of pages through a website leading to a destination page – in this case, a policy. A person will make quick evaluations of those pages based on how well suited they are to completing their goal. In an interesting behavioural study by Peter Pirolli and Stuart Card, this was likened to animals foraging for food, they called it ‘information foraging‘.

“Each source of information emits a ‘scent’ — a signal that tells the forager how likely it is that it contains what she needs.”

Information Foraging: A Theory of How People Navigate on the Web

Universities have not been particularly good at providing clear indicators in content that help users ‘forage’ for information successfully and recognise it when they see it. This is especially true for policy type content, often because very little attention or thought is given to how it will be represented on a website and how people interact with it. The publishing process often ends when the content is finalised in Word and saved as a PDF which is then uploaded to the web. A reliance on PDFs means that a print mindset still dominates thinking for how policies are consumed in a digital medium.

Badly structured policy content often forces the user to read or scan the entirety of the content before they can decide whether it’s the information they were looking for. Plain English summaries are a rarity. Labels such as policy, procedure, statement, and regulations are used interchangeably with little consistency and so rendered meaningless. There’s little or no attempt to think how this kind of information maps onto a person’s mental model of the different kinds of subjects it might cover.

What we’re doing

Clearly there’s lessons we can learn to improve the overall user experience around corporate information.

To ensure this content is searchable on the new University website we’ve given it structure using a content type called ‘corporate information’. A content type is basically a reusable collection of fields in our content management system (you’ll probably come across content types for ‘course’, ‘guide’, ‘facility’, ‘story’, and others as you navigate the new University website). Structuring content around content types has many benefits but the most obvious one for users is that it allows them to narrow their search to one specific type – in this case ‘corporate information’.

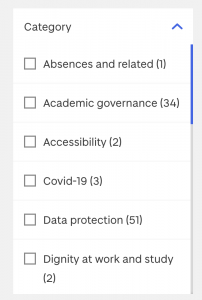

Content types combined with the power of taxonomies allows us to categorise content. In this case we have created the three taxonomies below which relate to corporate information.

Corporation information type

Because we’re using ‘corporate information’ as a fairly broad brush for all sorts of compliance or procedural content, this taxonomy provides a way of segmenting it into different types. ‘Policy’, ‘procedure’, and ‘disclaimer’ are just some of these.

Corporation information category

The category taxonomy gives us the ability to associate items with broader thematic areas. Think of the anxious employee in the scenario I highlighted earlier, instead of them trying to understand our organisational hierarchy they can view a list of all work/life balance policies from our website search

Groups

‘Group’ is one of the terms that you’ll see a lot on the new website as it connects lots of different types of content. A group represents part of the University’s organisational structure – for example a School or Directorate and, within these, departments, services etc. A group will have responsibility for a policy so we can indicate this to the user in the content.

These three taxonomies combined gives users some very flexible ways to filter content.

Accessibility

There’s a strong reliance on presenting policy and related content on organisational websites (including this one) in PDF format. There’s many reasons for this. The source document for a policy is often a version controlled word document and, as I mentioned earlier, it’s easy to export this a PDF. Policies are sometimes long and often contain design elements that make more sense in print rather than viewed in a browser. It’s often assumed that PDF is a better format because the user will print then read the content.

PDFs are a hard habit to break for organisations but the new digital accessibility requirements should make many think about that addiction.

As a university, we are now compelled by law to ensure our digital content can be accessed by as many people as possible. All content (including PDFs) should be accessible to people with:

- impaired vision

- motor difficulties

- cognitive impairments or learning disabilities

- deafness or impaired hearing

PDFs are not a particularly accessible format. Documents have to be marked up to ensure that people using screen readers can navigate the content and identify sections, headings, and images. It’s often a jarring experience with users presented with unnavigable content and layouts which only make sense when printed.

We should think carefully before adding a PDF to a policy and ask if it would be possible to provide the same information as part of the content of the page rather than as a download.

Migrating content

We’re now working with key contacts across the University to migrate existing content into the new website. Just as importantly, we’re beginning to define the guidance for publishing corporate information. User testing and feedback from staff will of course be vital as we do this. The end result should be policies and other types of corporate information which are easier to find, more readable, and accessible.